The 'time' of painting has always moved in multiple directions, and all of that movement (not to mention what we call memory) is incapable of being anywhere except the present.

*

Gena Rowlands, in a still from "A Woman Under the Influence."

*

The universe that Dante inhabited was orderly, complete, and completely known. The universe we inhabit is 95 percent dark matter and dark energy, about which we mainly know what they are not. The more precisely we are able to measure and analyze, the more mysterious everything becomes. We are the first humans to realize that our stomachs are incredibly complex ecosystems whose ramifications we barely grasp. To put it another way, here we are in the vastness of the cosmos, and we don’t even understand our own stomachs.

'I’m not chasing utopia; I’m chasing wholeness and power. Every narrative I explore, no matter how far back I go, involves catastrophe. But what I’m really interested in is what comes next—how we survived. We’re still here, so what happens after the disaster?'

Sevigny knows what she’s supposed to say about aging—that it’s a wild ride into uncharted territory, that older women and the natural changes that come with the passage of time deserve to be represented onscreen. But honestly, she’s annoyed by the whole thing: “The second adolescence or something? There’s some term. But it seems more difficult than adolescence because I’m menopausal and all that. Hormonal changes.” (And in case you’re wondering, no, she has not read All Fours, Miranda July’s perimenopausal novel. “Sounds intolerable,” she says when I describe the plot.)

The task that generative A.I. has been most successful at is lowering our expectations, both of the things we read and of ourselves when we write anything for others to read. It is a fundamentally dehumanizing technology because it treats us as less than what we are: creators and apprehenders of meaning. It reduces the amount of intention in the world.

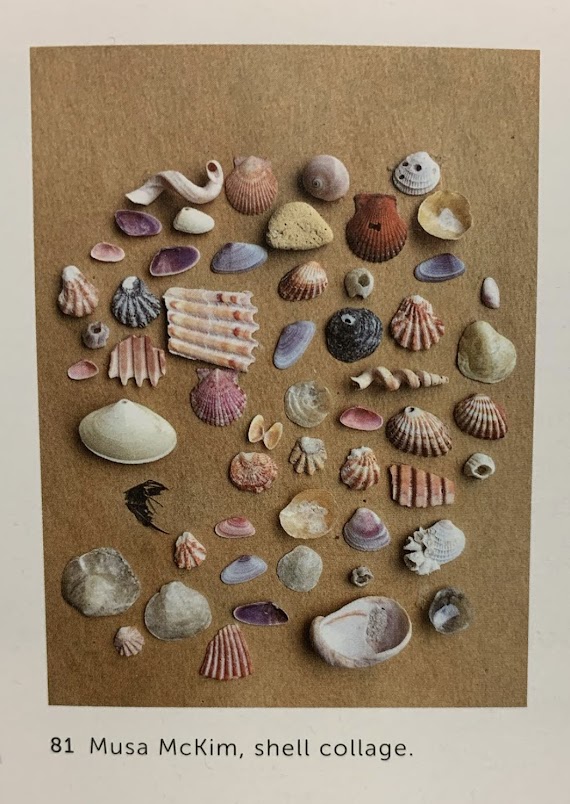

How much of my time is spent thinking about style, fashion, clothing, decorating, fabrics, pattern, quilting…. So what if those are ungrand concerns, “feminine” concerns…. the visual statements that have moved me—many of them—were made from small ideas, unpretentious ones that were big after all.

She wore an oversized olive-green sweater, wide-legged black satin pants, and chunky pale-pink sneakers; her hair was white and cut in a blunt, chin-length bob with a center part, and around her neck she wore a gold chain with a pendant of green glass. She was chic and easy in her manner, but life at her age is far from effortless, she said. Since Vicky’s death, Ducrot has been increasingly dependent upon Wijesundara, who has worked for her for forty years. 'She washes me,' Ducrot told me at one point. 'I am completely in her hands.' As we sipped our champagne, Ducrot explained that the happiness she felt was not unqualified. 'I am terrified also, naturally, because friends of mine, old people, are dying,' she said. 'But happiness is another thing. I think I am helped by the words that come to me—words are more generous with me now.'

Her treasures range from seventeenth-century Tibetan prayer shawls to fragments of Egyptian cotton dating possibly to the ninth century. Vicky collected Indian miniature paintings, becoming a self-taught expert. On their travels in Yemen, Uzbekistan, and elsewhere, the Ducrots gathered cuttings of wild roses—transporting damp stems in their suitcases before planting them at their country house, in Umbria, where they tended a garden exclusively dedicated to the genus. It still supplies flowers for Isabella’s apartment.

The Book of the Queen’s Doll’s House contains a fascinatingly weird essay by the engineer Mervyn O’Gorman on the 'effect of size' on the dollhouse’s world. It’s a known bugbear in miniature-making that certain materials don’t perform well at scale: an inch-wide cotton coverlet sits on the dollhouse bed like a piece of cardboard, for example. But Mr. O’Gorman must have been the first writer to seriously consider the physics of the miniature. According to his calculations, the little people living in the dollhouse—he called them 'Dollomites'—would have the strength of ten men. They’d eat six meals a day, leap staircases in a single bound, and have hearts like hummingbirds. Their voices would be inaudible to us; the gramophone and working pianos in their house would cause more pain than pleasure to their tiny ears. To the Dollomites, the paint on the walls would be a half-inch thick, and a single drop of water from the tap the size of a pear. Every glass of wine would be so viscous they’d have to suck it down. And forget about soup. 'Cream or thick soup,' O’Gorman warned, 'would be so sticky that the soup spoon would be found to lift the plate with it from the table.'