For a long time, we ignored them. They were easy enough to ignore, anyway, for most of us. People who knew things said there really was no problem, no problem. Some insisted no, that something had to be done, but they were in the minority; mocked, gently at first, but with escalating intensity that tilted toward cruelty, toward real division. But then, in certain circles at least, it began to be known that the people who knew things had secret doubts, that they were sharing their fears in closed, private conversations, amongst themselves, in encrypted chats and secure conclaves. They were making plans and arrangements for themselves, and actually, the government was involved, all the way to the highest levels.

Because, of course, we did see them. Everyone could see them. You couldn't help seeing them. They were there, always there, lingering under overpasses, huddling in parking garages, under bridges, in abandoned houses and the broken industrial spaces we'd outgrown, in the weed-tangled margins. Even if it was just a glimpse from a car window, shadows caught by the corner of an eye. Eventually the problem could not be denied. There were just too many, too many and always more, and pundits argued about what we had done, why their numbers were increasing, how to address the problem, what responsibilities, if any, we might bear, as if we could've helped it.

They were gathering, you see. And there were so many, so many; the old spaces could not hold them. They began to creep into our houses and garages, in basements and attics and garden sheds, taking up residence in any little-used corner. That is when we knew that something had to be done. They could not be left to fill the spaces we had made. It was too upsetting—the realization that they were there, always there. And knowing what they represented, what it meant. It shook us, even the most stolid, the most unfeeling, the hardened and unimaginative being paradoxically highly susceptible to the strange feelings their presence occasioned. We were unsettled; that was the word for it, unsettled. We were troubled, uneasy.

Perhaps those feelings fed them; the research was inconclusive. We did not quite understand how they were sustained, what it meant to exist that way. But what mattered is that we began to suffer from them. Health outcomes declined. Property values and overall productivity were adversely impacted. Children were fractious and restless; petty crime went up. They needed to go; we wanted them gone.

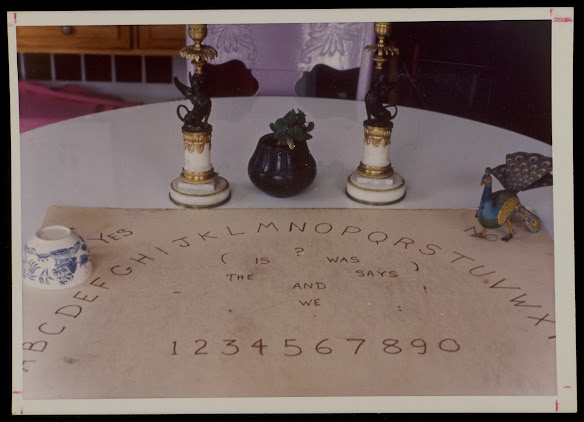

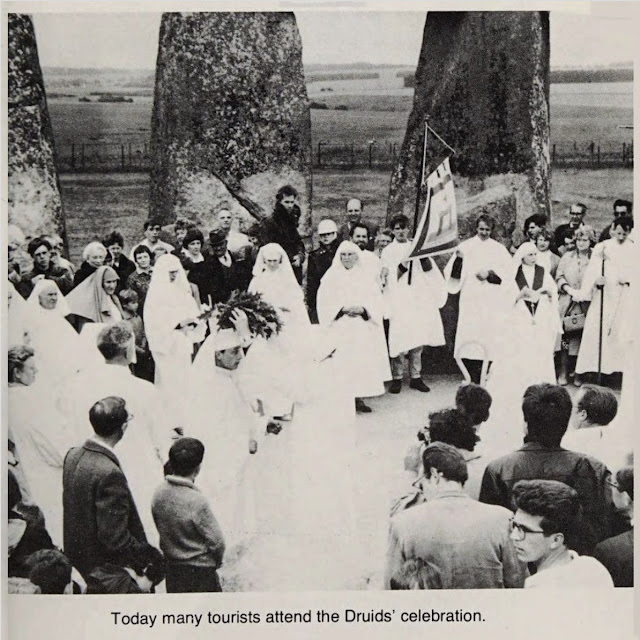

Different approaches were tried, even the old rituals, but the breakthrough came when a researcher discovered not only a method of capture but a means of distillation. A deep vault would be dug, and they could be stored, bottled, alongside the other indissoluble problems we had made. The problem had been solved.

Once they were gone, finally gone, though, we were no happier. No, we felt a strange jitteriness, a nagging discomfort, a feeling as if we had left something important undone, like the oven was on or the door was unlocked. We did not remember feeling that way before, not all the time, but there it was. Their going had left a space we could not tolerate. Theories shifted; perhaps, indeed, they were somehow necessary. The breakthrough came when it was discovered that their distillate was injectable—well-tolerated in human subjects, with minimal side effects—a gentle bruise, a passing malaise. Doses were made available, enough for all, but most especially the young and old and lonely, who were peculiarly vulnerable to them. Once they were in us, safely in us, and we knew they were there, we could rest again.