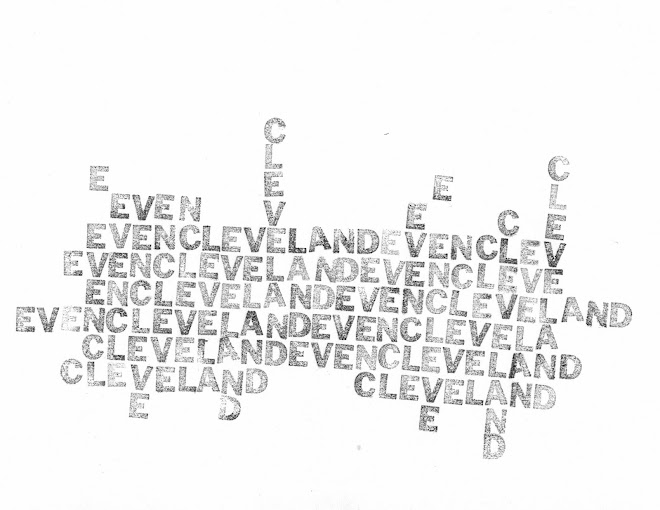

A song for Halloween.

I smashed your pumpkin on the floorIt's a sad song with a funny backstory (explained in the clip above — you can listen to a clip of just the song here).

The candle flickered at my feet

As goblins flew across the room

The children peered into the room

A cowboy shivered on the porch

As Cinderella checked her watch

A hobo waited in the street

An angel whispered, trick-or-treat

But what was I supposed to do

But to sit there in the dark?

I was amazed to think that you

Could take the candy with you too

My brother was singing this to Hugh last week while my mom and I cleaned up after dinner, and I wondered how many horrible breakups a person has to go through to write like that. She laughed, and said I was underestimating imagination — which was true. I forget that I know (knowledge smothered beneath giant, tome-like biographies minutely tying lives lived to work produced, endless (endless!) personal essays, and so many people seemingly going everywhere and doing everything) that personal experience only matters so much in creating something extraordinary.

A comfort, as I pick up pieces of small wooden fruit for the seventeenth time today.

On that theme:

Dayna Tortorici writing about Elena Ferrante:

Ferrante has caused a minor crisis in literary criticism. Her novels demand treatment commensurate to the work, but her anonymity has made it hard. The challenge reveals our habits. We’ve grown accustomed to finding the true meaning of books in the histories of their authors, in where they were born and how they grew up, in their credentials or refreshing lack thereof. Forget the intentional fallacy; ours is the age of the biographical fallacy.

...

Ferrante knows that authorship is never the isolated work of an individual artist; the author owes everything to those she remembers. “There is no work of literature that is not the fruit of tradition, of many skills, of a sort of collective intelligence,” she told the Paris Review. “We wrongfully diminish this collective intelligence when we insist on there being a single protagonist behind every work of art.”'*

Julie Phillips' profile of Ursula K. Le Guin:

To talk to Le Guin is to encounter alternatives. At her house, the writer is present, but so is Le Guin the mother of three, the faculty wife: the woman writing fantasy in tandem with her daily life. I asked her recently about a particularly violent story that she wrote in her early thirties, in two days, while organizing a fifth-birthday party for her elder daughter. “It’s funny how you can live on several planes, isn’t it?” she said.