We watched The Souvenir a few weeks ago. It captures some part of filmaker Johanna Hogg's own experiences as a privileged young woman in 1980s London and moves along two enmeshed axes: her fumblings toward becoming a filmmaker and her affair with a charismatic man addicted to heroin. The film obsessively recreates Hogg's material world, folding in her own love letters, student film projects, even clothes, and furniture. I'd wanted to see it right after I read Rebecca Mead's profile of Johanna Hogg. What sold me was this:

In an entry from 1988, Hogg wrote, “Everyone congratulates her on how well she is coping with it. Ironic because she isn’t ‘coping’ with it at all—she won’t allow herself to.” But Hogg didn’t tell that story, or any story, for years. She didn’t release her first feature film until a decade ago, when she was forty-seven, and “The Souvenir” is only her fourth movie. This summer, Hogg is shooting “The Souvenir: Part II,” a continuation of the story of Julie’s early adulthood. Together, the films will implicitly tell another story: that of a female artist’s belated emergence in middle age, and her discovery that she could create art out of experiences that had once seemed like lost time.It's a marvelous movie. We watch Julie, Hogg's stand-in, move through a series of experiences. She is laboring to create a movie that she can't quite explain. She goes from meeting Anthony, a somewhat older man who is both not quite what he seems and completely what he seems, to somehow being entwined in his life. Time passes; maybe years. The basic plot points—bad boyfriend, struggling artist, privileged background—do not coalesce into any sort of expected, pocketable narrative. Their meanings are suspended. The viewer is never quite sure how Julie understands these things—we only glimpse her in the process of living them, of trying, maybe, to make sense of them, but not yet fitting them into whatever narrative she will make of her life. It all remains irreducible to any sort of easy shorthand. This opacity—threaded through with kindness and cruelty and generosity and misunderstanding—felt so authentically human to me that I was startled to see it on a screen.

Beyond my own wolfish need for unboring storytelling and any story having to do a woman becoming an artist in the second part of her life (ha), I relished the subtlety of the costumes. Julie dresses like three different people: while writing or at school, in jeans and plaid shirts and fatigue jackets and white sneakers; with her wealthy family or on dates with Anthony, cashmere cardigans, silk scarves, brooches, menswear coats, and sensible flats; on a lovers' trip to Venice, like the costumed heroine in a 1940s movie wearing pearls, a custom nipped-in grey skirt suit and a trailing satin gown, shimmery as a slatey sky, with matching opera gloves. Demure girlish-frumpy pajamas and vixenish lingerie (Anthony's gift). There is a quality of playing dress-up in whatever she wears that felt so true to my own memories of being in my early twenties; that these clothes are all hers, but not quite her, maybe, so much as ideas and expectations she can wear.

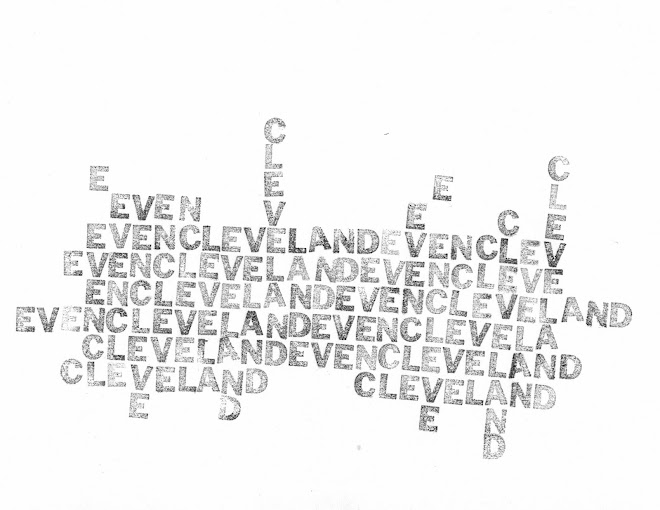

This outfit is much more somber than what you'll find in the movie; my late-summer mood skews a bit dark and severe, I guess. But things I am taking from it to make my own this fall: menswear coats (this is a 2012 Isabel Marant Etoile) / plain jeans / cashmere cardigans / silk blouses / pearl earrings / wristwatches / typewriters / symbolist opera / buckled shoes. Also: plain white sneakers and knife-pleat skirts and satin ball gowns. And a willingness to keep flailing toward expression.