Giving books can be somewhat fraught, at least according to The New York Times, so I've organized these by hypothetical recipients, expanding beyond the usual categories to encompass some giftees that might be particularly tricky. These are not exactly grouped by age or genre; it's a happy jumble.

We'll start with some easy ones ...

For the littlest readers:

In the Town All Year Round by Rotraut Susanne Berner. A possibly perfect book, nearly wordless, with so many stories to discover in the cutaway views of a town and its residents moving through a year, losing and finding things, including pets and wallets and love.

Contrary Dogs by élo. Fun and funny, this deceptively simple pop-up book is worth reading to smithereens, because tugging ears and tails to transform ridiculous dogs is irresistible.

The Chirri and Chirra books by Kaya Doi. Two cherry-cheeked children pedal through a gentle world of dreamy adventures, including soaking in hot springs scented with flowers, snuggling with friendly badgers, and making tourmaline candies. For even briefer adventures that skew surreal and gnomic, try the Sato the Rabbit books by Yuki Ainoya.

For picture-book fanciers:

Professional Crocodile by Giovanna Zoboli and Mariachiara Di Giorgio. A dapper crocodile wordlessly goes about his sophisticated, surreal urban life. (Look for the cheetahs in the Metro.)

Du Iz Tak? by Carson Ellis. A book of bugs written in bug language; 10/10.

Mr. Watson's Chickens by Jarrett Dapier and Andrea Tsunami. Mr. Watson's love of chickens nearly causes his loving (and extremely tolerant) partner, Mr. Nelson, to fly the coop, but the flock finds a surprising new home just in time. (Sidebar: For more chicken drama with a helping heap of quantum physics, see Skunk and Badger.)

For readers of chapter books:

The Arabel and Mortimer books by Joan Aiken. The hilarious adventures of a sweet child named Arabel and her agent of chaos/sulky, opinionated, and ever-hungry raven, Mortimer. (I have read each of these books aloud at least four times in the last six months.)

The Real Thief by William Steig. Steig stories are like Montessori knives; scaled for children, but they cut. This compact tale is about a goose accused of stealing, and, of course, the identity of the real thief. Steig encompasses complicated issues like justice and blame, obligation and forgiveness with an empathy, humor, and wisdom that eludes many so-called grown-up novels.

The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay. A grumpy, opinionated pudding that never runs out and can become whatever its owner wants it to be causes hijinks involving a sailor, a koala, and a penguin bold, members of The Noble Society of Pudding Owners.

For fantasists:

The Adventures of Anatole by Nancy Willard. A compilation of wonder tales involving the surreal quests of a kind boy named Anatole who occasionally finds himself in the company of talking cats and girls made of glass and women who can make the weather.

The Gormenghast books by Mervyn Peake. Any time anyone ever asks me to recommend a book, I will recommend this one, even though I know this a book readers need to find for themselves: it is so rich and strange and singular and unforgettable.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke. Oh, I love this book. Do you secretly yearn to wander grand, decaying marble halls that stink of the sea and echo with waves? To unravel mysteries written in bone? To step into the other world that shadows our own? Then this is the book for you!

For young (and old) adults:

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. Boarding school coming-of-age with a bioethical twist.

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler. Hunger Games and its ilk are weak sauce; slip the kids in your orbit the hard stuff. They can take it. And after they read this, they may cross categories and become ready for the next category ...

For doomsday preppers:

The Wall by Marlen Haushofer. Overnight, the world changes, and a woman finds herself alone, with only a cat, a dog, and a cow for company. What does it take, and what does it mean, to survive? (One of the best books I read in 2022.)

Harrow by Joy Williams. A teenaged girl wanders, looking for a home; meanwhile, radical oldsters foment futile acts of ecoterrorism in a world of epic environmental degradation. A savagely funny, piercing read.

For romantic scientists:

The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science by Richard Holmes. I think I have read this three or four times now; it's wonderful, absorbing fun, delving into the conceptual pivot that happened in the late 18th century as modern scientific thought started to coalesce, and tracing astounding discoveries and feats of ingenuity that shaped the world of science as we know it. It's also how I learned about Caroline Herschel, comet-sweeper.

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut. While some may sniff at the liberties this book takes in imagining the processes of mind that lead to the signature scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century, they should get over themselves, because this is an exhilarating conjuring of, to steal from Holmes, the beauty and terror of science, how what's possible can change, and dark shadows cast by brilliance.

For curious gardeners:

Brother Gardeners: A Generation of Gentlemen Naturalists and the Birth of an Obsession by Andrea Wulf. An engrossing look at the early 18th-century partnership of John Bartram and Peter Collins—Bartram collected seeds and saplings from across the colonies of what would become the United States and sent them to Collinson, who was in England, remaking English gardens forever. Wonderful for anyone who has wandered through a garden center and wondered where a plant came from.

Among Flowers: A Walk in the Himalaya by Jamaica Kincaid. Kincaid's memory of a seed-gathering expedition in the Himalayas is sharp, unsparing, and spellbinding, a look at the strange places our hunger for beauty can drive us, and the unsettling relationships and power dynamics that result.

For the irreverent:

I Am God by Giacomo Sartori. So, God is *maybe* having an existential crisis? And then there's this woman—he can't stop watching her, though he really has better things to do. In this, his diabolically funny diary, he tells all and vents about the woeful problems of being an all-powerful deity.

Accidental Gods: On Men Unwittingly Turned Divine by Anna Della Subin. A wildly entertaining account of actual "accidental gods"—humans venerated as deities, usually in their lifetimes and often under protest. (Think Christopher Columbus, James Cook, Douglas MacArthur, Haile Selassie, Gandhi, various petty colonial administrators, and, tragically, Donald Trump.) Like spaghetti strands twining around a twirled fork, the stories of these happenstance gods wind into one big bite: the story of how whiteness became divine, the ultimate false idol to overthrow.

For the solastagic:

The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy by Michael McCarthy. A beautiful and enraging, deeply personal account of the denudation of the natural world.

Mariposas Nocturnas: Moths of Central and South America, A Study in Beauty and Diversity by Emmett Gowin. A gorgeous, heartbreaking documentation of over 1200 species of moth, individually photographed and arranged in 51 grids of 25, based on when and where they were seen. The plentitude of moths, each so special, each so particular, seen all together, intoxicates, a visual manifestation of our great dumb luck in getting to live alongside such creatures, though of course we (meaning me, meaning humanity in the aggregate) are our doing our relentless best to ruin their world as fast as we can.

Gigantic Cinema, edited by Alice Oswald and Paul Keegan. A selection of poems and excerpts culled from various writers organized to chart the changing weather of a single day.

For mathematicians and spies:

Dr. No by Percival Everett. This book is about nothing. It's hilarious.

For noir enthusiasts with an appreciation for the surreal:

Strange Beasts of China by Yan Ge. Human-like beasts and beastly humans mysteriously coexist in an industrial city somewhere in China where it always seems to be dark and rainy, and one woman is determined to sleuth the origins of the strange creatures around her, creating a singular field guide to the oddities and sorrows of their lives.

For people who only read mysteries:

Miss Pym Disposes by Josephine Tey. You gotta stick with this one til the end; it's not what you think.

For bell-ringers (and people who only read mysteries):

The Nine Tailors by Dorothy L. Sayers. I have read this four or five times, and each time, I marvel at what Sayers accomplishes here—not only patterning a whole book around the obscure practice of change bell ringing (the "traditional English art of ringing a set of tower bells in an intricate series of changes, or mathematical permutations (different orderings in the ringing sequence), by pulling ropes attached to bell wheels"), but also writing a mystery of profound humanity. One of her four greats, alongside Murder Must Advertise, Gaudy Night, and Busman's Honeymoon.

For evil financiers and crypto enthusiasts:

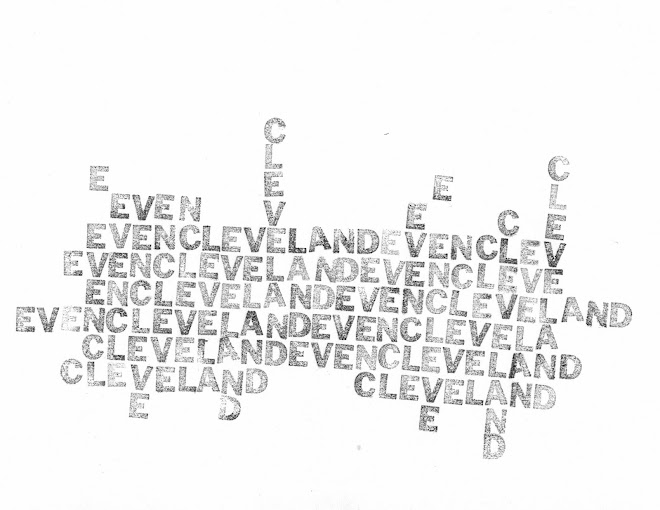

JR by William Gaddis. Let's just say the investments don't go to plan. (And if you happen to know an art forger or a sun-worshiper, Gaddis has them covered, too—try The Recognitions.)

For clout-chasers:

The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton. The story of the canny and orchestrated Gilded Age rise of Undine Spragg, who if she lived now would totally have, like, 400k followers and a wellness MLM.

For the complicit:

All for Nothing, by Walter Kempowski. For a German family at the end of World War II, life goes on as usual—until it doesn't, and their comfort and inaction exacts an epic cost.

For the misunderstood, in sympathy with their sore, wild hearts:

O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker. This is the only novel Barker wrote (it was published when she was 51), but why bother writing more if you can write something as absolutely perfect as this? Here, Barker relates the story of Janet, whose brief life is shaped by place and misunderstanding and circumstance as she grows up in a world of squalid privilege in mid-century Scotland. The feeling for nature is extraordinary, as is the depiction of the ways that innocence can be misconstrued and misunderstood, and how difficult it is to be a self that does not fit in the world in the expected ways. This is writing that reveals the gap between what is commonly considered beautiful and true sublimity.

*

One more bookish thing: I am trying out bookish newslettering; if you are interested in intermittent dispatches on what I am reading and what I thought about it, with links to blog posts, here's the link.

*

A sidebar on giving books: Sometimes, it's hard to get a copy of the exact book you want in time for whatever occasions giving it. When that happens in our family, we like to take a page from elementary school days when kids sometimes got to draw replacement covers for library books (those books were always the most fun to check out, anyway). We scribble out our own version of the cover and give that with a promise that the book is coming soon (the handmade covers make for funny and memorable bookmarks).

*