The holiday season is careening toward culmination—candles lit, songs sung, gifts exchanged, a new calendar unwrapped—and as usual I don't feel ready.

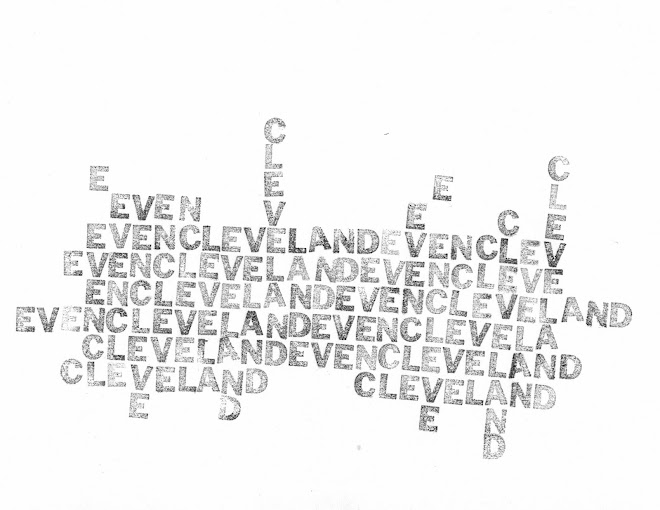

(That's me above: the blockhead groping her way toward 2026.)

To steady myself, I like to look at my books, because they hold time differently. With stacks around me, I am rich in options: each book a door, each door a different future. And the books are patient, waiting for the moment when, for obscure reasons, I am ineluctably compelled to pick up the book a friend gave me three Christmases back or that one I bought for $.50 at a library sale, start reading, and feel my whole self electrified with thought and art.

(I tend to roll my eyes when people get breathy about BOOKS and WRITING and the POWER OF WORDS, but damn if it isn't true.)

Anyway, this is why I think books are the most exciting gifts. Here are a few I'd recommend.

For picture-book lookers, any age:

Any book by Tana Hoban, maker of the best photographic picture books. Hugh and I were particularly fond of Shapes, Shapes, Shapes, Is It Red? Is it Yellow? Is it Blue?, Is it Larger? Is It Smaller?, and Red, Blue, Yellow Shoe.

For bedtime-story listeners:

Giovanni Rodari's Telephone Tales: "Every night, at nine o’clock, wherever he is, Mr. Bianchi, an accountant who often travels for work, calls his daughter and tells her a bedtime story. Set in the 20th century era of pay phones, each story has to be told in the time that a single coin will buy."

Grace Lin's Where The Mountain Meets the Moon, the story of Minli, who leaves the Fruitless Valley to find the Old Man of the Moon.

For struggling artists:

Randall Jarrall's The Bat Poet, which Elizabeth Hardwick described as "a haunting little story, a parable of charming instruction—and of instructive charm." It tells of a bat who sees what other do not and has to learn what to do with that knowledge, gently dipping into questions of poetic meter, criticism, and craft.

Rumer Godden's An Episode of Sparrows, the story of trying to realize a creative vision and how support can make all the difference. (More about it from me here.)

For anyone longing to draw the sun:

Bruno Munari's Drawing the Sun.

For lovers of November walks among tatter-leafed trees:

In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World, excerpts from the writings of Henry David Thoreau, selected by Eliot Porter. Porter's quiet photographs of the natural world capture the stillness of ephemeral places in a way that pierces the soul. (There is a new edition by Chronicle, which is fine, but the original edition, designed by David Brower, is miles better.)

For museum wanderers:

John Berger's Portraits, a collection of essays about artists which in its scope and variety of forms is akin to wandering an expertly curated gallery of the mind.

For New Yorkers in exile:

The WPA Guide to New York City, a time-machine and teleportation device disguised as a book. Compiled and published in the 1930s as part of the New Deal effort to keep writers and artists employed, it captures the bones of the city as it was then, a skeleton still visible in many places, through capsule histories of neighborhoods, buildings, and services. (It is also how I discovered the amazing House-Number Key to Manhattan.)

For bourgeois anarchist cooks:

The transporting, mesmeric, fabulous, and maddening Honey From a Weed by Patience Gray. In her forties, the English-born Gray upended her comfortable life as a successful cookbook author to follow the sculptor Bernard Mommens to the Mediterranean. In his quest for stone, they lived in remote areas of Greece, Italy, and Spain, and Gray committed herself to rural life, absorbing and recording a dizzying array of culinary folkways. The book, published in the mid 1980s, is absolutely singular—reminisces of seasonal feasts and meetings with rare book collectors sandwich a chapter on anarchy—and crammed with a plethora of extremely specific, plainspoken recipes that range from the simple to the terrifyingly time-intensive. (One that requires poking the seeds out of grapes with a pin haunts me.) Gray's unsentimental admiration for the resourcefulness of the communities she lives in is obvious, and yet much of what she admires is a reality shaped by brutality—foraging less as a delightful diversion and more as a desperate need to make as many things as possible palatable.

Print out Angela Carter's 1987 LRB review, which digs into the uneasy question of Gray's privilege, as a side dish:

The metaphysics of authenticity are a dangerous area. When Mrs Gray opines, ‘Poverty rather than wealth gives the good things of life their true significance,’ it is tempting to suggest it is other people’s poverty, always a source of the picturesque, that does that. Even if Mrs Gray and her companion live in exactly the same circumstances as their neighbours in the Greek islands or Southern Italy, and have just as little ready money, their relation to their circumstances is the result of the greatest of all luxuries, aesthetic choice.Offer Pulp's "Common People" as an apéritif.

For people who experience transcendence listening to Philip Glass:

The Philip Glass Piano Etudes Box Set, a printed object to treasure forever.

For solo francophiles:

French Cooking for One by Michèle Roberts, a beguiling and practical mix of memoir and microfeasts.

For women who want it all:

Family Happiness by Laurie Colwin. Polly Solo-Miller Demarest has more than enough— a loving if overworked husband, two charming children, a close (maybe too close) extended family, a fulfilling job, a fabulous apartment, access to a vacation spot. She is meeting expectations. She should be happy. She is happy. And yet ... maybe she wants something more? Colwin is so terrific at rendering humans on the page, WASP-ishly frayed collars and all, that reading this book feels like crashing a great party, and WHAT AN ENDING. I am deeply aggrieved that no female filmmaker of the 1980s or '90s made this into a movie (paging Joan Micklin Silver), because it deserved to become a repeat-watch classic.

For lovers of Victorian gossip:

Five Victorian Marriages by Phyllis Rose digs into the savory eye-popping marital foibles of Thomas and Jane Carlyle, Effie Gray and John Ruskin, Harriet Taylor and John Stuart Mill, George Eliot and George Henry Lewes, and Charles and Catherine Dickens. It is redolent with the inimitable tang of actual books-in-stacks library research, distilled through Rose's wry, subtly opinionated sensibility.

For the handsy:

Jeux de Mains by Stephen Ellcock and Cécile Poimbœuf-Koizumi, a book that must be handled carefully, as the credits for its 100 images of hands lie hidden within the French-folded pages.

For undead grammarians:

The Deluxe Transitive Vampire: The Ultimate Handbook of Grammar for the Eager, the Innocent, and the Doomed by Karen Elizabeth Gordon, to enliven the study of a languishing art.

For zombie-fanciers:

It Lasts Forever and Then It's Over by Anne de Marcken. Perhaps the only book I have ever read where the protagonist ends up decapitated and yet the narration carries on.

For death-defiers:

Elias Canetti's lifework, The Book Against Death, and Douglas Penick's retelling of the Vetala Panchavimshati, The Oceans of Cruelty: Twenty-Five Tales of a Corpse Spirit (both discussed here).

Also Jenny Erpenbeck's The End of Days, a book where the protagonist dies again and again.

For practical gardeners:

Bill Neal's Gardener's Latin, an invaluable little volume that decodes plant tags.

For unsentimental Ohioans (and anyone who appreciates fantastic novels):

Dawn Powell's My Home is Far Away. Gore Vidal, in a killer 1987 profile in the NYR, says "For decades Dawn Powell was always just on the verge of ceasing to be a cult and becoming a major religion." Reading this novel was my conversion experience.

For unforgettable tales of murderous and mysterious boarding school life:

Our Lady of the Nile by Scholastique Mukasonga and Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay.

For seasonal dressers:

Fletcher's Almanac: Nature Encounters and Fashion Systems Through the Year by Kate Fletcher, a singular tying of the sartorial to the seasonal that includes advice like "use the winter months to enlarge the pockets of your clothes" and "practice seeing fashion shows and collections as imitations of breeding displays and nesting activity" and links crop tops to spider silk.

For ambitious readers with short attention spans:

Hanuman Editions, tiny works of avant-garde writing.

For the pathologically nostalgic:

The Good Old Days: They Were Terrible! by Otto L. Bettmann which cheerfully and thoroughly demolishes the notion that the past in the United States was ever, in any way, better. (More about it here.)

For puzzle freaks:

For the ruin-minded:

Rose Macauley's The Pleasure of Ruins, "an inquisition into the images, philosophy, theology, archaeology and literature of ruin. And, moreover, it is a book that allows its subject matter to infect its logic and form: it is a sprawling and enigmatic work; an excessive and truly stupendous book." (Look for the massive hardcover edition.)

For sky-gazers:

Ad from the New Statesman and Nation, March 2, 1940, via The Silver Locket.