The train snakes through the icy mountains, its steady, churning roar breaking the quiet of snow-stilled space. Inside, the traveler gazes idly out the window into the darkening world. An eight-rayed star and glittering snowflake shine from the shoulder of her structured copper cardigan, while wooden adornments dangle from her ears and circle her finger. Slouchy velvet trousers break for a gleam at the ankle, like the rare green flash of sunset, paired with a peculiarly sensible pair of soft shearling shoes. She taps one silvered nail against the glass, then reaches down into a startlingly capacious bag, crammed with things to read. She pulls out a gleaming metal book and opens a marble box of sharpened scented pencils. After ringing the buzzer for a pot of tea and a fresh pear, she turns her attention again to the bag.

Inside, there is Edmund de Waal's "book about archives that is itself archival," Bridget Penney's recreation of a book that "contained enclosures ... and that encompasses all that can be captured through the filter of the writer's gaze and mind," and writings by Jenny Erpenbeck on things that disappear. There is Paul Willem's The Cathedral of Mist, telling of "the emotionally disturbed architectural plan for a palace of emptiness; the experience of snowfall in a bed in the middle of a Finnish forest; the memory chambers that fuel the marvelous futility of the endeavor to write; the beautiful woodland church, built of warm air currents and fog, scattering in storms and taking renewed shape at dusk," and a novel by Maurguerite Young that David Shurman Wallace asserts "eschews any stable sense of reality." He described his emotions reading it:

As I waded through dense paragraphs of long, winding sentences filled with images of stars and waves and angels, of seagulls and silk and butterflies, of dreams and illusions and any other abstraction you can imagine, occasionally I felt angry—on a personal level—at what I took to be the book’s obstinacy, its willingness to reprise what it had said hundreds of times before, not to mention the seemingly endless detours that defy any obvious sense of structure. At other moments, I knew that I was immersed in something beautiful and strange, something too big to understand all at once.

There is also a rare collection of Young's essays with her 1945 piece, "The Midwest of Everywhere," because this is a place, too, that the traveler calls home:

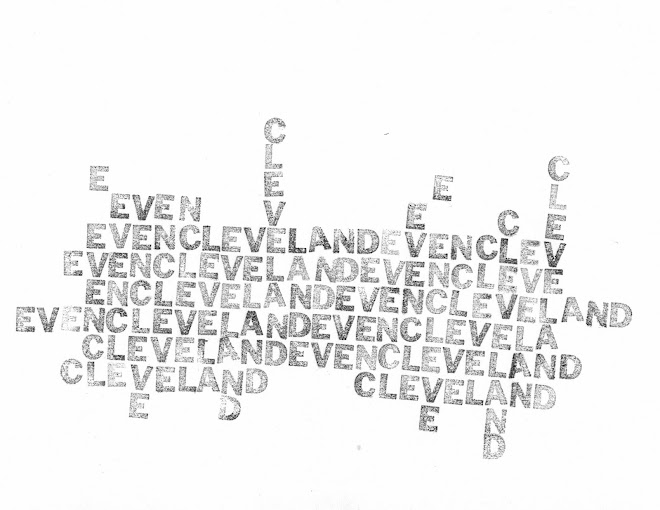

For me, a plain Middle Westerner, there is no middle way. I am in love with whatever is eccentric, devious, strange, singular, unique, out of this world—and with life as an incalculable, a chaotic thing, meaningful above and beyond the necessary and elemental data of my subject ... I am told by commentators both cynical and wistful, those who have never inhabited my regionless region, that we of the Middle West have no Main Stream, no focus, no elite. 'True,' I would answer, 'the Middle West, though it may have a hidden Gulf Steam, has no Main Stream because it is oceanic'—that is, touching on all shores and limitless. There are no boundaries I know of. I have seen, on the grassy ocean, many a lurching ancient mariner—and once, in an Indiana cornfield, a dead whale in a boxcar.

The Middle West is probably a fanatic state of mind. It is, as I see it, an unknown geographic terrain, an amorphous substance, the ghostly interplay of time with space, the cosmic, the psychic, as near to the North Pole as to the Gallup Poll.

There are more hefty tomes to consider: a "death-defying feat of ambition ... a spectacular honeycomb of books within books" and a 544-page monograph on Celia Paul, which recalls to the traveler's mind an afternoon in an airy London gallery being held by painted eyes. A unforgettable exhibit of Surrealist and Romantic work is catalogued, as is "five centuries of stars, dreams, and plenilunes" and 2,000 Japanese rain words. Smaller books fill the corners—late ghost stories by Henry James, a book of "melancholic, wandering castles," another with photographs of hands, and one tense with high-stakes mountain drama.

The traveler thinks. What does she want to read? After all, it is Christmas Eve. Finally, she finds what she is looking for—a book of Yuletide hauntings.

Merry everything, friends.

*

Other jólabókaflóðs (Yule book floods).

*

TOGA PULLA Motif cardigan / Album di Famiglia velvet W & S trousers / Susan Hable ebony drop earrings / early Victorian carved bog oak mourning ring at Erica Weiner / Jean Gerbino cup and saucer, ca. 1950 / Lizzie Ames custom journal cover / Hender Scheme Mouton Henri shoes / Harry and David pears / Choosing Keeping x Perfumer H scented pencils / Maria La Rosa Verdino laminated socks.