After the passage of draconian abortion laws in Ohio, Georgia, and Alabama, I thought it might be useful to look at child poverty to see how these allegedly "pro-life" states are doing at creating a "pro-life" culture.

So, let's talk about the children. Per the Children's Defense Fund, in the United States:

Nearly 1 in 5 children—12.8 million in total—were poor in 2017. Over 45 percent of these children lived in extreme poverty at less than half the poverty level. Nearly 70 percent of poor children were children of color. About 1 in 3 American Indian/Alaska Native children and more than 1 in 4 Black and Hispanic children were poor, compared with 1 in 9 White children. The youngest children are most likely to be poor, with 1 in 5 children under 5 living in poverty during the years of rapid brain development.

All three states have the dubious distinction of being leaders in the number of children under six living in extreme poverty—defined as "an annual income of less than half of the poverty level or $12,642 a year, $1,053 a month, $243 a week or $35 a day for the average family of four."

That same report also offers a ranking by state for how many children live in just regular old poverty—defined as an annual income below $25,283 for the average family of four—$2,107 a month, $486 a week or $69 a day—as of 2017:

These states are also among the worst when it comes to infant mortality, per the CDC.

- Alabama: 265,078 children living in poverty (Alabama ranks 46th out of 50 states, 50 being the worst.)

- Georgia: 519,099 children living in poverty (Georgia ranks 39th.)

- Ohio: 513,231 children living in poverty (Ohio ranks 35th.)

Alabama, Georgia, and Ohio also have terrible maternal mortality rates. Alabama averages 18.7 maternal deaths per live births, Ohio 19.2, and Georgia a staggering 48.4.

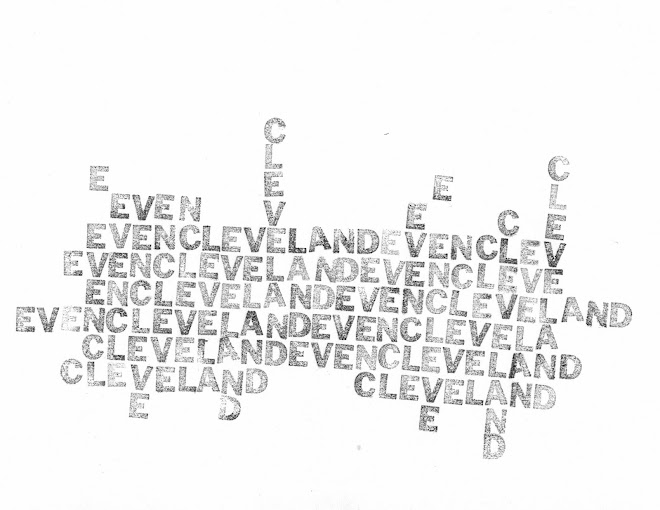

It's hard to square these statistics with a so-called "culture of life." I live in Ohio and I can tell you that it is not a "pro-life" state, and it is certainly not pro-child. Beyond the 500,000 children living in poverty, the public schools are poorly funded (the public school funding system has been unconstitutional for 22 years). In Cleveland, thousands of children are suffering from lead poisoning while lawmakers in Columbus offer zero help or support (they have found the time to pass anti-woman legislation and fund all the legal challenges that will follow). Guns are everywhere. Ohioans are dying of opiods and social services are struggling to support the children left behind. I could go on; the examples are many.

As someone who actually cares about supporting human lives, the hypocrisy is appalling. But that's because these laws have nothing to do with a "culture of life" and everything to do with "imposing a moral judgment on women for having sex."

It's horrible that so many people are having to share traumatic personal stories and open themselves up to harassment to try and reach the hard hearts and thick heads of abortion opponents. But lives are at stake. In The New Yorker, Kate Doloz wrote about explaining her grandmother's death after an illegal abortion to her daughter:

To understand Win’s story—what had happened to her, what she had done, and why—my daughter would need a number of moral and biological concepts that were not yet in place in her young mind. Still, I wanted to offer her a simplified version of the truth that could remain stable for her as she got older. I wanted to assure her that, even though this was a story she needed to grow into, she should always feel free to ask questions, and that I would answer as honestly as I could. And I wanted to break my family’s long-standing silence surrounding Win’s death, because silence only helps to perpetuate the fallacy that outlawing abortion has ever stopped women from attempting it.

If I couldn’t immediately explain to my daughter how Win died, I decided, I could at least explain why. “She needed help really badly and no one would help her so she died,” I told her. Then I added a reassurance that I’m not sure I’d feel confident offering today. “It’s not a thing that would happen to us now,” I said. “If we ever needed that kind of help, we would get it and we would be safe.”

*