Sometimes when I say that I didn't like a particular book, someone will tell me that of course I didn't like it—it wasn't "for" me, and what did I expect. This comment is aggravating not because it hurts my fragile feelings to be told I am outside of an author's ideal audience, but because it makes plain that a dismaying number of very smart people seem to understand books fundamentally as products slotted for specific consumers. God, how depressing! Imagine being satisfied reading only what is "for"—or marketed—to you. Why read at all if you aren't reading to encounter something outside yourself?

Anyway, I think one of the books I read this week is, actually, for everyone. Emmet Gowin's Mariposas Nocturnas: Moths of Central and South America—A Study in Beauty and Diversity documents over 1200 species of moth, individually photographed and arranged in 51 grids of 25, based when and where they were seen (you can see one here). Gowin spent 15 years on this project, traveling to Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, French Guiana, and Panama, in the company of scientists, setting up a light behind a sheet at night to entice the moths. Some he gently moved, placing them against printed backdrops of favorite artworks before he photographed them, and those particular photographs, with the moth's breathtaking patterns and colorations against blurred, zoomed-in image fragments, have a fragile, hallucinatory beauty that made me forget I was looking at a photograph–they felt like rediscovered illustrations from the brush of some nameless, long-forgotten, supremely skilled natural artist.

The potency of the moths' dazzling individuality is not obscured by the grid; instead, the plentitude of moths, each so special, each so particular, seen all together, intoxicates, a visual manifestation of our great dumb luck in getting to live alongside such creatures, though of course we (meaning me, meaning humanity in the aggregate) are our doing our relentless best to ruin their world as fast as we can.

In his essay, Gowin says that it took him five years to photograph the first five grids; this, after years of photographing the moths and not quite knowing what the photographs would become, getting just one or two images from 30 rolls of film. Reading about this process made me think of Simone Weil's essay, "Attention and Will":

The poet produces the beautiful by fixing his attention on something real. It is the same with the act of love. To know that this man who is hungry and thirsty really exists as much as I do—that is enough, the rest follows of itself.

The authentic and pure values—truth, beauty and goodness—in the activity of a human being are the result of one and the same act, a certain application of the full attention to the object.

Teaching should have no aim but to prepare, by training the attention, for the possibility of such an act.

All the other advantages of instruction are without interest.

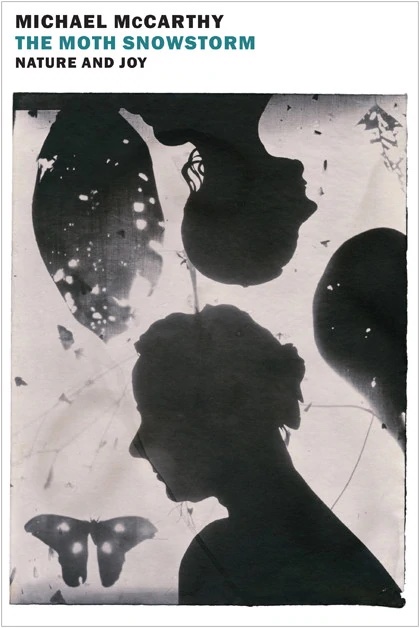

It also recalled another beautiful book I read sorrowing over the diminished abundance of the natural world: Michael McCarthy's The Moth Snowstorm. One of Gowin's photographs is on the cover.

*

Images:

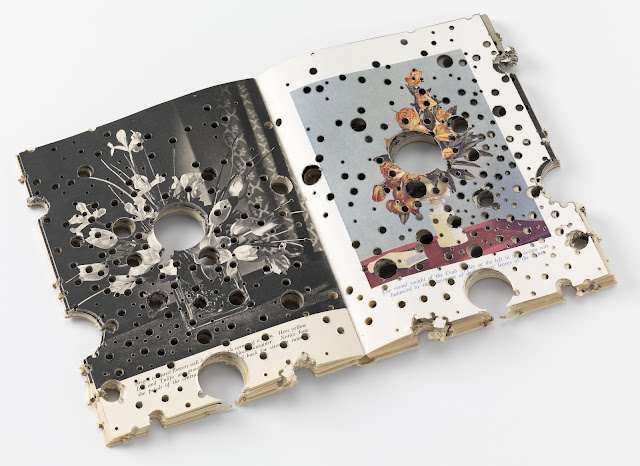

Jonathan Callan, Around the House, 2005. National Museum of Norway.

Cover of The Moth Snowstorm.

1920s Hand-colored postcard of Arizona's petrified forest.

*