After ending 2021 reading Rachel Cusk's Second Place—a conglomeration of ideas about art and art-making tenuously bound by the structure of domestic novel with a narrator of both frightening acuity and near-total obliviousness (a plethora of exclamation marks; the unmissable signal of an unbalanced mind!)—I took to the mountains.

First, I read Scott Ellsworth's The World Beneath Their Feet: Mountaineering, Madness, and the Deadly Race to Summit the Himalaya, an enthusiastic, sprawling, sometimes repetitive account of British, German, and U.S. expeditions to various summits in the Himalaya in the 1930s and 40s, ending with the eventual successful summit attempts on Everest/Chomolungma (1953) and K2 (1955).

They wore cotton parkas and scratchy woolen sweaters, and they climbed five miles into the sky wearing leather hobnailed boots while carrying wood-handled ice axes and heavy coils of manila rope. They slept in drafty canvas tents and tried to cook their meals on fickle kerosene-fueled stoves. They drank brandy and smoked cigarettes, read Dostoevsky and Dickens at 24,000 feet, and they gutted our restless nights only to discover, in the dim light of dawn, that a foot of snow had sifted on top of their sleeping bags during the night.

There is a dizzying cast of characters (the capsule biographies at the end of the book were welcome) as well as a staggering number of well-supplied expeditions to recount (and Ellsworth is particularly good at the details when it comes to listing all of the esoteric items the quail-in-aspic school of gentlemanly mountain climbing deemed necessary for a proper expedition—a staggering display of ego—though he is prone to flashy, melodramatic sentences, especially as the scenes shift). Fascinating here, alongside the tales of grand (usually doomed), increasingly geopolitically motivated expeditions, is the emergence of a new style of more egalitarian mountaineering, one with a lighter footprint that finally started to value the places en route and around the summit— notably in Terris Moore, Richard Burdsall, Arthur B. Emmons, and Jack Young's attempt on Minya Konka in 1932, and Ang Tharkay, Kusang, Pasang, Eric Shipton, and H.W. Tilman's journey to Nanda Devi through the perilous Rishi Ganga Gorge in 1934. (Throughout the book, Ellsworth shines some welcome light on the extraordinary achievements of the Sherpa climbers who were present on almost all of these endeavors.)

One of the dreamers who pops up in Ellsworth's book is the focus of Ed Caesar's The Moth and the Mountain: A True Story of Love, War, and Everest. (Another grandiloquent subtitle—got to fit those key words in for the algorithmic gods, I guess.) Maurice Wilson was a decorated British World War I veteran who decided to fly to Mount Everest and become the first person to climb it, having never flown a plane or climbed a mountain. Rory Stewart's 11/17/2020 review in the NYT gets to the problem: "Caesar is a fine writer, but he has not managed to find the art to resurrect a man whose final act is so bereft of context or explanation." Parul Sehgal might diagnose Caesar's issue as an infatuation with the trauma plot. He tries to extract motivations from Wilson's war service and even grasps at flimsy rumors of Wilson's possible proclivity for cross-dressing to find a why that is not there. It's particularly frustrating because in the beginning of the book, Caesar writes that "there is never one fact or secret about a life that explains someone." Well, d'oh!

Sadly, both books lack the true hallmark of a great mountaineering book—cold. I never felt cold while I was reading them. Maybe a slight shiver from the Ellsworth.

I want to read Eric Shipton's book about Nanda Devi now and maybe finally get to John Roskelly's accounting of the harrowing 1976 Indo-American expedition to the mountain. And both Caesar and Ellsworth mention Wade Davis's Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest, though I may pick up Robert Macfarlane's Mountains of the Mind (still my favorite of his books) to re-read his artful reconstruction of the Mallory climb instead.

Much like climbing a mountain exposes a climber's weaknesses, writing about mountains exposes an author's. Ellsworth and Caesar both show technical skill, but lack imaginative capacity—their stories, vivid in themselves, struggle to come alive. The Living Mountain put their weakness in sharp relief. Nan (Anne) Shepherd (1893-1981) lived near the Cairngorm mountains in Scotland—puny bumps compared to Himalayan majesty–and yet, though a lifetime spent walking and being in their presence, she found majesty there.

This, finally, was the book I needed, after a year spent close to home. A book that took me somewhere else while reminding me that I, too, live in a place of wonder (because any place, observed and experienced closely, holds wonders). Organized into twelve short sections, Shepherd tunes her attention to every aspect of the mountain–its rocks and water and weather, the animals and plants and people that call it home—and her own physical experience of being in mountain space, of tuning her attention to its frequencies, of walking herself into new states of awareness and being.

Written in the 1930s, the book laid in a drawer until its publication in 1977. The edition I read included a wonderfully perceptive introduction by Robert Macfarlane (and a crabbed closing essay by Jeannette Winterson pettishly lauding the power of reading—yawn). Macfarlane writes:

Most works of mountaineering literature have been written by men, and most male mountaineers are focussed on the summit: a mountain expedition being qualified by the success or failure of ascent. But to aim for the highest point is not the only way to climb a mountain, nor is a narrative of siege and assault the only way to write about one.

Shepherd writes beautifully about how she came to know the mountain—"to know, that is, with the knowledge that is a process of living," a knowledge that "does not dispel mystery"—and how that knowledge has changed her—"place and mind may interpenetrate till the nature of both is altered."

It's a book that makes you want to stop reading and go outside for a walk.

*

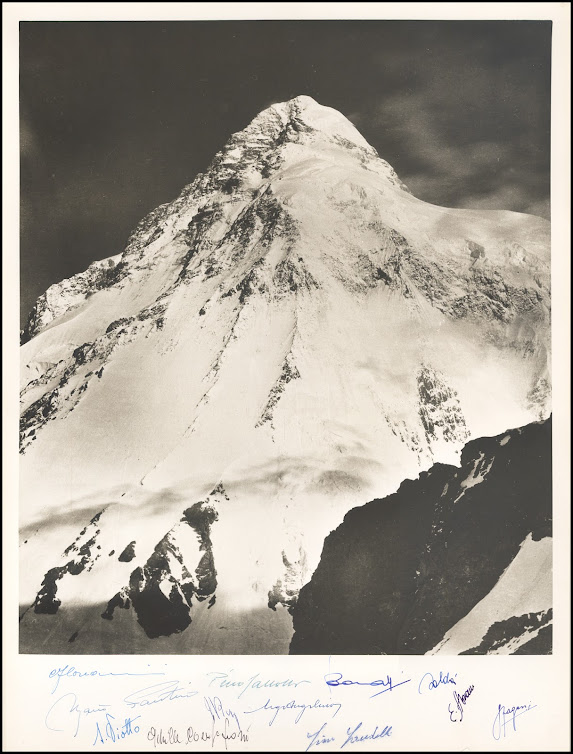

Images:

An image of an 1903 expedition to Kangchenjunga.

First edition of Eric Shipton's Nanda Devi at Shapero Rare Books.

Folio Society edition of The Living Mountain.