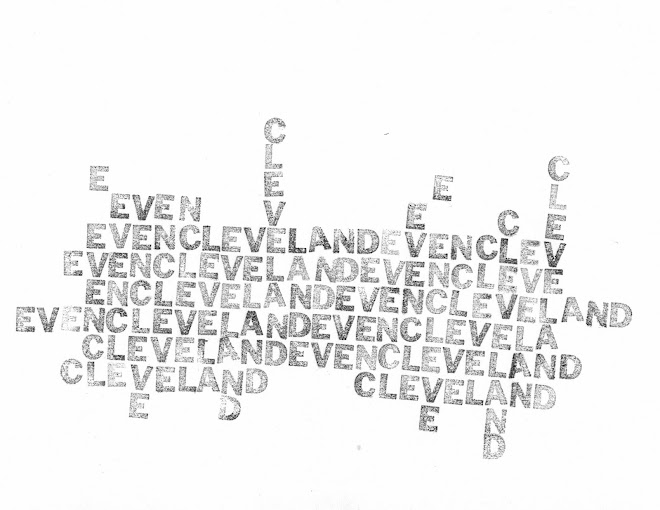

Manuscript of Emily Dickinson's poem 466:

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

*

“This woman who wanted me always to feel possible.”—Jasmine Mans, describing her mother in Broccoli, Issue 11.

*

I have been pregnant three times. My first pregnancy ended in abortion at 11 weeks, my second pregnancy resulted in a child, and my third pregnancy miscarried. Each time, I willingly chose to enter that space of uncertain possibilities that surrounds pregnancy. Each time, I did not know what to expect, though after that first time, I knew something more about how little anyone can actually know about what to expect when you are expecting. After the second, I was somewhat wiser about how vast and ongoing the commitment to another life is. And the third revealed just how callous practices of care directed toward pregnant people can be. I will not forget walking past all the cozy delivery rooms to access the grubby little curtained alcove where I got a D & C.

To take away what choice a person can have in such an uncertain undertaking as pregnancy, to say to someone, no, you must do this thing, this thing that will radically reshape your life and body and future, is cruel. I do not understand a “love” that looks past the person in front of you, the person who knows their own life, the person who has made a decision, the person asking for help, to prioritize protecting a pulsing clump of cells. Alive, true. But not a life, not yet. Just a possibility.

I wonder about these people, so enamored of blastocysts, of embryos—“a thing at a rudimentary stage that shows potential for development”—that they will demand its potential take precedence over the actualities of the living person sitting in front of them. Is it easier for them to love something abstract and unknown, something that can still be whatever they imagine it to be? Easier than loving actual humans, who can only be what they are? Such hubris, to know better what someone’s options should be. Of course, the fact of being the sort of human who can get pregnant continues to preclude full personhood in our culture, though a few of us may become CEOs and billionaires and whatever else. Better protect the flickering cells, the ones that could actually become a real person, provided it has the correct chromosomes.

This is a reality like a massive mountain, maybe too massive to see the scope of until the light hits right, and it’s illuminated in its awful vastness. And whenever that happens, when some of us realize yet again that we still are not really seen as actual people, we start sharing our very real stories to assert our full personhood, something only white men and fetuses are granted here in the United States. My feeds this week are full of people sharing their abortion experiences. There are people who didn’t think twice about having an abortion; others, like me, who grieved but felt relieved; still others who later regretted it. And after these outpourings, the certain circle these stories like vultures, picking for narrative morsels that feed their arguments. It’s exhausting.

No single story ever encapsulates any human experience. And I am increasingly wary of stories, anyway. The ugly power of narrative is evident everywhere in this country. Maybe what we need is to step away from storytelling—the repeated tales of what a mother is, of what a person should be—to dwell in possibility. Why is what we do with our bodies endlessly up for debate, whether that is choosing not to be pregnant or getting the care needed to align an inner and outer self? Why are people so afraid of making space for choice? Of accepting that people do, in fact, know what is best for them, in a way others can’t?

What a tragedy to spend fifty years trying to shut a door rather than change the path that leads to it. (See here: the evident hypocrisies in the anti-child policies of so-called pro-life states). What a tragedy that so many people still feel that what they most want is others to have less, not more. What a tragedy that we still have yet to embrace the full bewildering glory of actual human potential.

What I want most for my child is that whoever he is or wants to be feels possible. But I also want him to realize, in such a foundational way that it shapes everything he understands, is that radical possibility extends to everyone around him—that no one is a story set in stone, that everyone is always changing, always becoming. That choice is freedom, and everyone deserves to be free.

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

*

“This woman who wanted me always to feel possible.”—Jasmine Mans, describing her mother in Broccoli, Issue 11.

*

I have been pregnant three times. My first pregnancy ended in abortion at 11 weeks, my second pregnancy resulted in a child, and my third pregnancy miscarried. Each time, I willingly chose to enter that space of uncertain possibilities that surrounds pregnancy. Each time, I did not know what to expect, though after that first time, I knew something more about how little anyone can actually know about what to expect when you are expecting. After the second, I was somewhat wiser about how vast and ongoing the commitment to another life is. And the third revealed just how callous practices of care directed toward pregnant people can be. I will not forget walking past all the cozy delivery rooms to access the grubby little curtained alcove where I got a D & C.

To take away what choice a person can have in such an uncertain undertaking as pregnancy, to say to someone, no, you must do this thing, this thing that will radically reshape your life and body and future, is cruel. I do not understand a “love” that looks past the person in front of you, the person who knows their own life, the person who has made a decision, the person asking for help, to prioritize protecting a pulsing clump of cells. Alive, true. But not a life, not yet. Just a possibility.

I wonder about these people, so enamored of blastocysts, of embryos—“a thing at a rudimentary stage that shows potential for development”—that they will demand its potential take precedence over the actualities of the living person sitting in front of them. Is it easier for them to love something abstract and unknown, something that can still be whatever they imagine it to be? Easier than loving actual humans, who can only be what they are? Such hubris, to know better what someone’s options should be. Of course, the fact of being the sort of human who can get pregnant continues to preclude full personhood in our culture, though a few of us may become CEOs and billionaires and whatever else. Better protect the flickering cells, the ones that could actually become a real person, provided it has the correct chromosomes.

Criminalization does increase the risk of physical harm. But that is basically a consumer protection argument: It’s not safe enough. The fact is that whether anyone ever climbed on an abortion table or not, the message of criminalization to all people who can get pregnant is: You don’t have dominion over your own body, you are always vulnerable, always in danger of being surveilled.

Historian Ricki Solinger, from "You Are Endangered as a Citizen." N+1, 5/5/2022

This is a reality like a massive mountain, maybe too massive to see the scope of until the light hits right, and it’s illuminated in its awful vastness. And whenever that happens, when some of us realize yet again that we still are not really seen as actual people, we start sharing our very real stories to assert our full personhood, something only white men and fetuses are granted here in the United States. My feeds this week are full of people sharing their abortion experiences. There are people who didn’t think twice about having an abortion; others, like me, who grieved but felt relieved; still others who later regretted it. And after these outpourings, the certain circle these stories like vultures, picking for narrative morsels that feed their arguments. It’s exhausting.

No single story ever encapsulates any human experience. And I am increasingly wary of stories, anyway. The ugly power of narrative is evident everywhere in this country. Maybe what we need is to step away from storytelling—the repeated tales of what a mother is, of what a person should be—to dwell in possibility. Why is what we do with our bodies endlessly up for debate, whether that is choosing not to be pregnant or getting the care needed to align an inner and outer self? Why are people so afraid of making space for choice? Of accepting that people do, in fact, know what is best for them, in a way others can’t?

What a tragedy to spend fifty years trying to shut a door rather than change the path that leads to it. (See here: the evident hypocrisies in the anti-child policies of so-called pro-life states). What a tragedy that so many people still feel that what they most want is others to have less, not more. What a tragedy that we still have yet to embrace the full bewildering glory of actual human potential.

What I want most for my child is that whoever he is or wants to be feels possible. But I also want him to realize, in such a foundational way that it shapes everything he understands, is that radical possibility extends to everyone around him—that no one is a story set in stone, that everyone is always changing, always becoming. That choice is freedom, and everyone deserves to be free.

*